Not Quite "Carlo"

- dmckee70

- Oct 23, 2025

- 7 min read

Verdi-DON CARLO: Gundula Janowitz, Shirley Verrett, Edita Gruberova, Judith Blegen; Franco Corelli, Eberhard Waechter, Nicolai Ghiaurov, Martti Talvela, Tugomir Franc/Vienna State Opera Chorus & Orchestra/Horst Stein, cond. (October 25, 1970); Orfeo C230163

This all-star performance has rarely been out of the catalogue. It enjoyed a stereo-LP release from Legendary Records, popped on mono CDs from Pantheon and has been legitimized by Orfeo. Last year, Naxos Deutschland renewed the license, so this is bound to stick around. What accounts for its enduring fascination?

Check out that cast: Can't miss, right? Well ... yes and no. A pair of renowned performances are caught on the wing, there are a couple of interesting near-misses and then there's Franco Corelli. Something for everybody—plus a couple of soon-to-be stars in cameo roles, in the comely forms of Judith Blegen and Edita Gruberova.

Be it known that this is four-act Don Carlo. No Fontainebleau scene. Given that Franco Corelli's grip on the title role was still slippery after singing for at least a decade, asking him to learn 25 minutes of new music was undoubtedly out of the question for the Vienna State Opera, whose previous stagings also fell into the four-act format. The present occasion was the premiere of a new Otto Schenk/Jürgen Rose production, one which would see 62 repetitions before being phased out in 1979. Blegen, Gruberova and Nicolai Ghiaurov would all move on after opening night, with Martti Talvela promoted to King Philip and Otto Wiener taking up the Grand Inquisitor's cassock.

The opera is foreshortened in more ways than simply the absence of Fontainebleau. It's arguably even more heavily cut than the State Opera's previous broadcasts. The scissors are first felt on page 85 of the Ricordi piano/vocal score, with Tebaldo's solo in the St. Just garden pruned (wasting the advantage of Gruberova). Rodrigo loses the second verse of his aria and Carlo's swoon at Elisabetta's feat is snipped. The B section of the Act II, Scene 1 trio is cut, making Verdi sound like a bad composer, and the auto-da-fe scene is shortened by a whopping 12.5 pages, swallowing up the role of the Herald.

Act III is spared the hedge trimmers but, per Corellian tradition, the marziale of the final encounter is AWOL, as are a page and a half of duet later (a tuck that catches Gundula Janowitz unawares). The real shocker comes at the end, when conductor Horst Stein—or was it director Schenk?—jump cuts from Carlo's last line to the coda of the opera: no Charles V, no shocked utterances from Philip, Elisabetta, Inquisitor, etc.

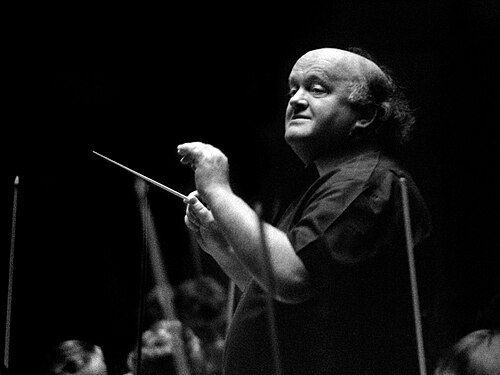

Speaking of Stein, he is the performance's most gratifying surprise. Indeed, he sounds gratified to have escaped Wagner Jail long enough to lead Verdi's grand opera. Stein would be further rewarded with Medea in 1972, demonstrating an unsuspected affinity for Cherubini's idiom. Here he proves himself an idiomatic Verdian, barring a misstep or two, such as the oafish underpinning of Philip's arrival at St. Just. The Vienna horns' opening chorale is persuasively sounded and a communicative podium presence is always evident. (Kudos also to the chorus, which is everywhere firm, idiomatic and impressive.)

The garden of I/2 is introduced with a charming lilt and the Act II preludio is purveyed with silken counterpoint. Stein tucks into the auto-da-fe with much slancio, although his Flemish Deputies (a lovely sounding group) sound far greater in number than the prescribed half-dozen. Act III's spectral introduction is beautifully rendered and his accompaniments are involving, especially in an exquisitely drawn Quartet. If Stein must bear responsibility for the heavy cuts, he also deserves credit for the splendid shaping of what remains.

Franco Corelli was the mainstay of Don Carlo revivals during the second decade of Rudolf Bing's reign. His volatility and matinée-idol looks certainly were apt. But he could be a handful, as he demonstrates here. At his entrance, he's rhythmically all over the place, with tone that tends to spread. Corelli substitutes all-purpose emotiveness for musicianship, and the performance is pervaded with so much imprecision of note values and rhythm that an overall nimbus of uncertainty descends. Stein has his hands full staying with the tenor. Careless about phrasing and words (unlike, say Shirley Verrett's Princess Eboli), Corelli is too often given to hokey emphases.

That being said, there are moments that are pure Corelli in a positive way, such as the stunning diminuendo that caps "Io la vidi." But he's oil and water with Gundula Janowitz's contained Elisabetta, dashing himself against her ravishing but restricted sounds. He challenges Nicolai Ghiaurov's King Philip with bracing authority (by contrast, Ghiaurov's plump, self-satisfied tones don't convey comparable meaning) and his typical plangency is put to good use in the prison scene. Corelli could be a law unto himself—a Miami Carmen from 1973 verges on the aleatoric—and one must either take it or leave it.

Like her contemporaneous Donna Anna for Carlo Maria Giulini, Janowitz' Elisabetta is a curate's egg. It's tonally recessed but musically impeccable and rather inscrutable. Is she neutral or simply being dignified, as befits a monarch's consort? (This Caesar's wife is far, far above even the appearance of impropriety.) She throws in a gorgeous glissando in the final bars of her garden duet with Carlo and gets both verses of "Non pianger, mia compagna." The latter is beautifully rendered, if without much point of view.

However, when wronged by Philip, Janowitz brings unwonted urgency and a sense of affronted dignity (her keynote in the role). She punctuates Eboli's confession of adultery with a most undignified whoop but redeems herself via a severe "Rendetemi la croce." The great and grandiose "Tu che le vanita" is surprisingly involving, with a rapt B section ("Francia!"). Janowitz's tone is as pure as ever and she basically pushes her chips to the middle of the table for this 10-minute scena. Stein is at one with her. (Had Janowitz been listening to some Meta Seinemeyer?) The only awkward moment is when she attempts a transition into "baby chest" voice. However, when faced with Corelli again, she retreats into impassivity. What's the opposite of chemistry?

Also frustrating is Ghiaurov's betrayed monarch. The bass dined out on the role for decades and I can't fathom why. Here he's vaguely apt without ever being "right"; Yes, his legato is burnished and splendid, but one cannot shake the impression of complacency. Also, Ghiaurov tends to shout when he needs to make a point. The dreamlike opening phrases of "Ella giammai m'amo" evince the first real feeling: Here is something to which Ghiaurov can relate. The aria is handsomely sung, if without the last degree of involvement. Also, he's cavalier about Verdi's markings there and elsewhere.

Ghiaurov is severely outfaced in the closet scene because he must go up against Talvela's super-baleful Grand Inquisitor. The Finnish basso's clenched tones convey implacability (as well they should) and his pulverizing sound dwarfs Ghiaurov. This Inquisitor is a very dangerous adversary, as when he crushes the Act III, Scene 2 uprising with memorable venom.

The other great performance on the premises is Shirley Verrett's Eboli. In the Act I, Scene 2 garden, there's a beguiling smile in her perfectly placed tones. Although some legatos become staccatos in the Veil Song (given uncut), her roulades enchant and help spark the first real signs of life from the audience. In her verbal fencing match with Rodrigo (Eberhard Waechter), she scores point after point. She's fiery and simply perfect when spurned by Carlo and "O don fatale" is a blaze of self-hatred, even if she and Stein take the middle section far too slowly.

Waechter is nobility personified as Rodrigo but this is not top-drawer Eberhard by any means. Vienna's resident Rodrigo and a Germanic singer with an Italianate style, he can be heard at his considerable best in a 1961 broadcast. Not so here. The intervening decade saw the baritone undertake overly heavy roles up to and including the Das Rheingold Wotan. The result can be heard in his frayed and worn tones. Triumphs still lay ahead for him: Alfred Ill in von Einem's The Visit of the Old Woman (1971), a Telramund under James Levine (1974) and Wozzeck for Christoph von Dohnanyi (Decca, OOP). He would even be the best A Survivor from Warsaw narrator I've ever heard. But Rodrigo no longer lies in his comfort zone.

Simply put, his tone has become too unsteady for Verdi. As sung by Corelli and Waechter, this Carlo and Rodrigo sound decidedly long in the tooth. Waechter has to simplify the gruppetti in the Act II, Scene 1 trio with Corelli and Verrett, and he is everywhere a sensitive interpreter—but one whose tone threatens to spread under pressure. The divisions of "Per me giunto" are beyond him now, although Rodrigo's death plays to Waechter's strengths: legato and believability.

Policing up the bit parts, we find Tugomir Franc holding forth as the cloistered Charles V, strained by the tessitura. But Judith Blegen's Celestial Voice is heavenly indeed, especially her chain of ascending trills. Two months later, Blegen would shoot to stardom as Marzelline in the Metropolitan Opera's bicentennial Fidelio. Small wonder, on the basis of her angelic sounds here.

If Corelli is the selling point, the only real competition is Sony's reissue of a 1964 Met broadcast of Don Carlo. And scant competition it is. Not that it lacks strengths. Giorgio Tozzi's multifaceted King Philip is everything Ghiaurov is not and Irene Dalis is a fascinating, dusky-voiced Eboli. Nicolae Herlea, in his Met debut, makes a sufficiently impressive Rodrigo to cause one to wonder why he only got 24 performances with the company. However ...

The Met chorus and orchestra are no match for Vienna's, especially under a conductor as slovenly as chorus master Kurt Adler. Leonie Rysanek is a committed Elisabetta but the role is an uncongenial fit for her voice. And Corelli is a chaos agent, nearly bringing the performance to a halt in the middle of the auto-da-fe when he simply fails to appear onstage. The mind reels at the fact that the Met found this near-catastrophe suitable for official release. Egad!

For those wanting an uncut, state-of-the-art Don Carlo, Giulini's EMI studio recording still takes the palm, even if the Grand Inquisitor is seriously undercast. I've not heard James Levine's studio version (Sony) but it restores the all-important opening scene that Verdi had to cut before the Paris premiere. As for the original version of the score, it is generally misrepresented on disc, with Antonio Pappano's clambake on EMI the worst offender. It is to musicology what Dr. Dulcamara is to medicine.

A legendary cachet adheres to Giulini's 1958 Don Carlo broadcast from Covent Garden and it has much to commend it, especially Boris Christoff's unforgettable King Philip. However, director Luchino Visconti was allowed to cut the score to shreds in an irresponsible fashion. It's well worth hearing, but best experienced as a pendant to an unabridged Don Carlo, preferably a Giulini- or Levine-led performance. Orfeo's Vienna performance is strictly for admirers of Verrett (also heard on Giulini/EMI) and Talvela (the Inquisitor of Sir Georg Solti's Decca recording) ... or for absolute Don Carlo obsessives. — David McKee

Comments